Trending Topics is a project that looks for statistical trends among news items- no opinions, no controversy, just the stats. I then use this data to draw a conclusion or make a prediction concerning current events, but I encourage readers to draw their own conclusions or comment on ways our research could be improved.

Saturday, December 8, 2012

Thursday, November 22, 2012

Do Consumers Have A Problem With Black Friday Creep?

Before I begin my post today I’d like to wish everyone a

happy Thanksgiving weekend, and safe travels to anyone visiting family or

friends today to celebrate the holiday.

While today is a day for being thankful, later tonight,

after the festivities, thousands of Americans will venture out later tonight

for the start of the holiday shopping season. Many stores are opening and

holding sales as early as 8:00 PM this year, and are being blasted for the controversial decision.

But exactly how much of a problem does America have with the

theory of “Black Friday Creep”? Many people say that this year the retailers

have gone too far- but will that stop consumers from going out and getting in

line early? Will we see yet another record-breaking sales period? It’s time to

see just exactly how hypocritical we are.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

If there’s one thing we can be certain about, it’s that

retailers are opening earlier:

I picked seven major retail chains, most of which specialize

in different or all genres of retail. None of them opened before 5:00 in 2008.

All of them are opening at or before midnight this year. Even K-Mart and Sears,

which had both consistently been among the later openers, are welcoming

customers at 10 PM this Thanksgiving.

Opening stores earlier means that there is a greater range

of time for people to show up, meaning more customers and more profit. Whether

it is because stores are opening earlier or because Black Friday is simply

becoming more popular, more customers are showing up, stores are making more

money, and- if only slightly- individual customers are spending more money.

Now for a brief interruption about the Internet: Online

spending has been up recently too. Thanksgiving Day spending online was up 18%

last year, and Black Friday spending was up 26%. All told, Americans spent

$1.295 billion online over those two days last year.

Getting back to in-person shopping, let’s also look at the

percent change in total amount spent:

2009

was a down year by all accounts. Individual customers spent the least in that

year, and the total amount spent was just barely more than the last year. You

could conclude that the recession meant people stopped showing up, but the

increase in customers was pretty much the same as between 2007 and 2008.

Customers still spent nearly $350 individually on Black Friday in 2009,

suggesting that while a recession does have a small impact on most Americans,

it’s not enough to stop them from showing up and spending money on Black

Friday. And this makes sense- stores usually hold some of their best sales of

the year the day after Thanksgiving, making it one of the best days to go

bargain hunting on.

Since 2009, however, people are steadily spending more and

more.

Now here’s the bad news for retailers:

This graph essentially represents the derivative of the

customer graph (for calculus fans out there)- it’s the percent increase in

customers over the previous year. While more customers show up each year, the

percentage of those that are new customers is slowly but steadily going down.

This suggests that at some point- probably after the next few years- Black

Friday could top out in terms of customers.

However, I use the phrase “bad news” in a relative sense.

When Black Friday finally reaches its customer limit, a good 250-300 million

people will be coming out for the sales, each spending an average of about

$400. Not bad for retailers at all.

Just for fun, I’ll make some predictions on the type of

turnout we could expect for this Black Friday. About 250 million customers

(the data suggests 249.8) will show up, spending on average about $393.95.

This is actually about five dollars less than the average consumer spent in

2011. However, the spent overall will still increase- a grand total of $56.1

billion*

Let’s get back to issue I talked about at the beginning of

the post: the slow creep of stores opening earlier and earlier on Black Friday-

and Thanksgiving. Americans say they have a problem with it. Do they?

Not at all. The percentage of total customers on Black

Friday that show up at midnight is increasing at an incredible rate.

One-quarter of Black Friday shoppers were out at midnight in 2011, a jump of

over 600% from 2009. If the trend holds true, we could see nearly half of all

consumers out at midnight- or certainly before.

Many Americans are complaining about the Black Friday Creep,

but the statistics show that we secretly embrace it. Something needs to

drastically change in the average American’s mindset before retail chains put

an end to the creep. Until that happens- if it happens- store owners will

continue to open earlier and earlier, more and more customers will turn out,

and more and more money will be exchanged in the day after- and on-

Thanksgiving.

*Why don’t the numbers add up?

Most of my data was from the National Retail Federation. I’m guessing they took

a survey of Black Friday shoppers and asked them how much they spent for the

average individual amount. The number of unique customers is also probably

lower than the total here, because many people shop at more than one place on

Black Friday.

Tuesday, November 6, 2012

Friday, October 26, 2012

Can We Find A Trend In The Fungal Meningitis Outbreak?

Epidemiologists have some of the most intriguing jobs in the

world. No other branch of science can make an immediate impact akin to that of

the study of diseases. The fruit of diligent research can be life- no,

world-changing. And when an epidemic strikes, their fast actions can save

thousands of lives.

Kudos to the epidemiologists on the case of the recent

outbreak of fungal meningitis. I heard about the outbreak, and then one day

later they had already located the cause and were doing work to minimize the

damage done by the tainted steroids. Unfortunately, they can’t save every life,

and nearly 300 cases have been reported with a fatality rate of about 8%.

However, their quick work surely saved many more lives.

For my latest post, I’ve decided to play epidemiologist to

try an isolate a trend among the data for the meningitis outbreak. Is there a

reason that certain states have been hit harder than others? (Besides, of

course, the states that haven’t received the infected drugs, and obvious

comparisons like population)

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

The CDC website doesn’t have information on former outbreaks

of fungal meningitis (or if they do, they’re hiding it very well), and this

made my first idea- does this outbreak parallel previous outbreaks?- very

short-lived. However, the CDC did

have interesting statistics on another topic, which redirected my plan for this

post.

The fungal meningitis outbreak has apparently been

classified as a “Healthcare-Associated Infection” or “HAI”. The CDC tracks HAIs

in a variety of ways; one of them is an SIR value: Standardized Infection

Ratio. This value is found by taking the number of actual HAIs and dividing it

by a predicted number of HAIs. Lower numbers are better, and values under 0.5

are very good. Similarly, values over 1.0 are very bad- this means that the

included facilities are actually causing more infections than they’re projected

to.

Here is a chart of the SIR values (in 2010, the most recent

I could find) for all of the states where the tainted steroids have been sent:

These values are mostly good; Indiana is the only state with

a value above 1, and Michigan and West Virginia both have values under 0.5

(Remember that!)

You may have noticed that three states- Idaho, Minnesota,

and Rhode Island- don’t have SIR values on the graph. This is because SIR

values are independently submitted by health care centers, and some states

don’t have enough centers submitting information to the CDC for effective

calculation of SIR. These three states are some examples- less than five

centers submitted information over 2010, whereas most states have several

dozen.

Since the outbreak is a HAI, it would be reasonable to

assume that most of the infections occurred in states with high SIR values. But

that isn’t the case:

|

STATE

|

CASES

|

|

ILLINOIS

|

1

|

|

NEW

YORK

|

1

|

|

IDAHO

|

1

|

|

PENNSYLVANIA

|

1

|

|

TEXAS

|

1

|

|

NORTH

CAROLINA

|

2

|

|

MINNESOTA

|

7

|

|

FLORIDA

|

17

|

|

MARYLAND

|

16

|

|

NEW

JERSEY

|

16

|

|

OHIO

|

11

|

|

NEW

HAMPSHIRE

|

10

|

|

INDIANA

|

38

|

|

MICHIGAN

|

53

|

|

VIRGINIA

|

41

|

|

TENNESSEE

|

69

|

|

CALIFORNIA

|

0

|

|

CONNECTICUT

|

0

|

|

GEORGIA

|

0

|

|

NEVADA

|

0

|

|

RHODE

ISLAND

|

0

|

|

SOUTH

CAROLINA

|

0

|

|

WEST

VIRGINIA

|

0

|

|

TOTAL

|

285

|

Indiana, which had the highest SIR value, has quite a few

cases compared to other states. Michigan, however, had the lowest SIR value-

and has more cases than any state except Tennessee. But West Virginia, which

had the second-lowest SIR value, has zero cases.

Why is there variability in the data? One reason is because

not every state received the same amount of the infected drug. Only one

facility in West Virginia received the drug, compared to six in Indiana. Based

on the data, each facility that received a shipment of the steroid had about

3.8 infections. From this average, we can predict how many cases will occur in

each state:

This isn’t very good. We can take it our prediction one step

further by applying a state’s SIR to the predicted number of cases (for

example, Illinois: 11 predicted cases x 0.678= 8 predicted cases with SIR):

There’s still no strong correlation here between SIR and the

number of cases. We can calculate our own SIR values for these states using our

predicted number of cases and the number of actual cases. Unfortunately, when

we do this, only four states- the ones in blue on the data table and the

following graph- have SIR values that fall within the standard range of scores

(that is, the range of scores for all 50 states.):

|

| M-SIR represents my own calculated SIR value based solely on the meningitis statistics |

Quite simply, there’s no correlation between HAI SIR values

and the recent fungal meningitis outbreak. The only explanation I can come up

with for this is that most facilities used the tainted steroid believing it to

be safe, whereas with most HAIs the healthcare center should know how to avoid

the problem.

My data:

Note: All data as of October 21, 2012

Tuesday, October 9, 2012

How Successful Will The iPhone 5 Be?

When it comes to technology- and specifically, new products-

perhaps nothing is more anticipated than the iPhone. When the original iPhone

was released in 2007, it was the beginning of the Age of the Smartphones. Since

then, Apple has stayed on the cutting-edge when it comes to their iPhones, and

excitement and anticipation over technological leaps and bounds precede each

release.

Last weekend, Apple released

their new iPhone, the iPhone 5. Apple had had nearly a year since its most

recent phone, the iPhone 4S, to work on improvements. The major selling points

Apple hit on in its press

release were the physical features, hailing the new product as the

“Thinnest, Lightest iPhone Ever”. For this post, I thought I’d take a look at

that claim, and examine the evolution of the iPhone. Is it really the thinnest,

lightest iPhone ever? Is there anything that prior incarnations of the

smartphone did better? Just how much money is Apple making on the iPhone,

anyway?

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Apple has released a new iPhone fairly regularly- about once

a year. I won’t be discussing the technological advancements of the iPhone in

this post because it’s clear the iPhone has progressed substantially in terms of technology

(Siri, anyone? It’s something Sci-Fi authors could only dream about even

recently). Instead, we’ll be taking a look at the physical aspects of each

phone.

The following graph represents the change in width for the

iPhone over time:

As you can see, there’s clearly no change between this

generation and the previous two. However, the other dimensions of the iPhone 5-

height, depth, and weight- have

changed somewhat. Here are those graphs:

The iPhone 5 is significantly larger in terms of height over

its previous incarnations. However, the change shouldn’t be terribly noticeable

for anyone using the phone: Only about eight millimeters, or a little more than

the length of a red ant. It also results in a potential increase in screen

size, though again, not terribly noticeable.

The iPhone 5 is also easily the thinnest iPhone yet, with a

depth of only 7.6 mm. But is it really that significant of a change? The new

phone has only shed 1.7 mm. Remember that ant from earlier? 1.7 mm is about the

length of its head, maybe a little smaller. The change probably won’t make any

significant difference in the future.

The weight of the new iPhone is something Apple is

significantly proud about. They claim to have eliminated 20% of the weight of

the iPhone 4S (and they have, actually), but since the iPhone 4S was so light

in the first place (140 grams), is it really such a big deal? Let’s examine:

the iPhone 5 is 28 grams lighter, so imagine three pencils, or five quarters. I

suppose this could make up a fairly noticeable change- I’ve never actually held

and compared the two, so I’m just making an estimation. But again, the iPhone

4S was already very light, so Apple isn’t

actually saving the backs of millions of their customers (thank you, the

Onion).

I also measured some characteristics of the iPhone that

aren’t exactly physical: memory and battery life. We can easily see the change

in memory over the generations simply by looking at what was sold- the original

iPhone was sold in 4, 8, and 16 GB versions, and while every iPhone generation

has had a 16 GB version, it’s the smallest memory option for the iPhone 4S and

5, which have 32 GB and 64 GB variants.

Battery life is more interesting than storage memory. Audio

and Video battery life has gradually increased over the years (40 hours of

audio since the iPhone 4, and 10 hours of video since the iPhone 3G), but

standby life has a different trend. The iPhones 3G, 3GS, and 4 all had the most

standby life, at 300 hours. The iPhone 5 has three days less life than that. Apple can still claim that it has increased

the battery power, however, since the iPhone 4S only had 200 hours of battery

life.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Has Apple been doing enough to attract new customers and

retain their old ones? How have their iPhone sales done over the years? The

answer may surprise you:

|

| Black plots in the above graphs represent the first quarter of Apple’s fiscal year. Their first quarter falls over the holiday season, and so yields significantly higher sales and revenue. |

The iPhone has been a complete and utter success for Apple.

Sales per quarter after the release of each phone have, at the very least,

doubled. In the quarter after Apple released the iPhone 3G, it saw an 861%

increase in units sold. Yes, you read that number right: 861%. While each

iPhone slowly trends downward after release (I estimated a 25% loss each

quarter when a newer model was on the market), Apple still pulls in billions of

dollars each month, and could hit $100 billion of revenue for this fiscal year.

Even more promising for Apple is the first-weekend sales of

its new iPhone 5. Five million phones were sold, bringing in about $1.5

billion- more revenue than the original iPhone made in its entire run, and

nearly as many units sold.

Here is my data: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AnZrkjWWJajQdFNLdmtnYUxOR1ZlY2lfVHR1ZlpGZ0E

Bounds were determined in several ways, but should be viewed

as the maximum and minimum possible totals for each phone. We know that no

phone has sold $0, so we have to estimate the lower bound. The estimated exact total is

based on the 25% decay rate mentioned above and, barring the discovery of the

actual data, is a good ballpark figure for each phone’s sales totals.

Sunday, September 23, 2012

How Long Will The Syrian Civil War Last?

I didn’t expect the bombing of U.S. embassies in North

Africa and the Middle East when I began to research this post, but the current

state of affairs in that region- unfortunately- fits very well this topic.

It’s been nearly two years now since the start of the Arab

Spring. Since then, we’ve seen many changes in North Africa and the Middle

East. As the protests grew, they captured international attention. First,

Tunisia’s government toppled. Sparked by their success, perhaps, other protests

broke out across the region. Egyptians overthrew their own government less than

a month later, and then Yemen followed shortly afterwards. In Libya, a civil

war broke out, and the rebel forces were successful by the end of August. Many

countries have had governmental changes; many others are still seeing ongoing

protests.

The bombing in Libya, and subsequent anti-U.S. attacks and

protests, prove that the Middle East and North Africa aren’t as stable as we’d

hoped they’d be. We should have expected this, though. After facing civil wars

and major governmental changes, it would be surprising if a country wasn’t in turmoil. And turmoil is

exactly what we have. It’s sadly commonplace for a country to fall back into a

state of civil war and disorganization directly following a revolution.

How long will it take for things to stabilize in the region?

That’s tough to answer. It’s not like a civil war, which can end overnight. We

won’t wake up one morning to find that everything’s better. It will be a long,

slow process that will likely take years to finish.

Let’s turn our attention towards the bloodiest state right

now, the one still in the midst of a gruesome civil war: Syria. This war has

been ongoing for far longer than any of the other armed conflicts associated

with the Arab Spring, and shows no signs of stopping. How long will it be until

the war ends, and how will it end? That’s the question we attempt to answer

today.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

I compiled data on 45 different civil wars besides the

Syrian war. 43 took place since 1930 (20 since the year 2000- in green), and

the other two were the United States Civil and Revolutionary War, which will be

used only as standards for comparison. 9 wars took place in the Middle East (in

tan on the data table), 22 in Africa (yellow), and the rest took place

elsewhere in the world, mainly East Asia and Central and South America. 37

lasted longer than a year (in blue).

I found data for each war on the death toll, the total

population of the country (at the midpoint of the war), the percentage of the

population killed, and whether or not the group that was rebelling was

successful.

Below is a scatter plot of the death toll of each war vs.

when it started. Ongoing (most at low-level) wars are in red in each scatter

plot:

There’s no correlation between when a war began and its

total death toll. This means that we haven’t been killing more people with new,

advanced weaponry, but it also means the number of people dying in these wars

is going down.

Additionally, one of the more disturbing trends we’ve seen

recently regards the number of civilians killed in times of war. It’s very

difficult to find statistics on this matter, especially since most civil wars

take place in under-developed countries. However, in many civil wars, a vast

majority of the people killed aren’t the soldiers and combatants on either

side- they’re innocent civilians, killed by bombs or other atrocities. From the

limited data I found on this, I’d estimate maybe 90% of people killed in the

average civil war for the past thirty or so years were civilians.

The next chart is a plot of the percentage of the population

killed vs. the starting year of the war:

Again, there’s no correlation between the two.

Finally, here’s a chart of the results of each civil war.

Five are ongoing (four at a low-level), and two are listed as “N/A” because

those wars were a result of a power struggle shortly after a revolution:

Most rebels are actually very successful in civil wars.

About 1/3 of the civil wars I looked at ended with rebel victories. Another 13

ended in tentative peace agreements, which usually grants some demands of the

rebels. Only seven of the 43 wars I analyzed ended with rebel defeats.

Why is this? Simple: The rebels are fighting for much more

than the incumbent government. They want change, and will go to greater lengths

to get that change. We can see a smaller version of this right here in America

with- believe it or not- online and telephone surveys. The results of those

polls are often skewed towards change because the people that want change are

feel strongest about the issue are more likely to respond to the survey.

All things considered, the average death toll for the civil

wars I examined was 266,940, and the average percentage of the population

killed was 2.37%.

In the Middle East alone, the percentage of population

killed was very similar: 2.38%. Taking

into account African countries yields a higher percentage: 2.71%. For Syria,

this percentage means 535,000-610,000 people would die in the fighting- twenty

times the current amount. The 267,000 figure is much more plausible.

The length of the conflict is difficult to predict. The

average length from the data was 9.79 years; not counting ongoing conflicts, it

was 7.74 years. The figure for the Middle East alone was 7.87 years. The first number actually makes sense; at the

current rate, the death toll would reach 267,000 in a little under nine years.

Let’s compare this to the U.S. Civil and Revolutionary Wars.

The Civil War lasted just over four years, yet took the lives of 625,000

people, the vast majority of them soldiers.

The Revolutionary War, on the other hand, lasted over eight years- yet only

50,000 Americans were killed, with about 35,000 Europeans. Warfare has

certainly changed over the years- and not necessarily for the better. The

change from conventional battlegrounds has led to the deaths of many innocent

people.

Now, to conclude. Based on the data, I expect the civil war

in Syria will last about six or seven more years, and will cause the death of a

little over 200,000 more people- most of them civilians. I sincerely hope that

this prediction is wrong and the war ends quickly- but that’s not what the

statistics suggest will happen. History does say, however, that the Syrian

rebels stand a good chance of winning.

My data can be found here: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AnZrkjWWJajQdEt1LWlrWFFxaVZ5c2hFbUdHb2dpdEE

Friday, September 7, 2012

When Will The Next Big Hurricane Hit The U.S.?

I remember the coverage of Hurricane Katrina very clearly. I

woke up and immediately went to watch the news, and Katrina was just coming in.

We knew it would cause a lot of damage, but I don’t think anyone knew that it

would cause quite as much as it did. In the weeks afterward, the costliest

natural disaster in American history dominated the headlines.

I have a special reminder of Katrina every year: The

hurricane made landfall in New Orleans on my birthday. This connection makes me

think of the power of hurricanes annually- and they always fascinate me.

We like to think that we’re above the power of nature. We’ve

climbed to the top of the world, and explored the depths of the sea. We’ve

built buildings that are ridiculously high- it’s almost like we’re mocking

nature, pretending to be invulnerable. And then, something like Katrina

happens, be it a hurricane, earthquake, tsunami, anything; and it sends us

crashing- sometimes literally- back to earth.

This year, I had another reason

to think of hurricanes. On my birthday this

year, another hurricane- Hurricane Isaac- made landfall in New Orleans.

Thankfully, the damage caused by Isaac was nowhere close to the damage caused

by Katrina; however, it was a reminder: at any time, there could be another

hurricane just as strong as Katrina. So is there a way to predict when the next

“big one” will hit?

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

The attribute that makes natural disasters so powerful is

their unpredictability. Volcanoes may give a few weeks’ at max. Hurricanes form

and make landfall within a couple of days. We’ve vastly improved our tornado

warning system; now we have nearly fifteen minutes of notice! And earthquakes-

well, good luck. The 2005 hurricane season was especially unpredictable- we’ll

get to that in a little bit. But the variability of hurricanes is what makes

predicting the next powerful one especially difficult.

I could use all Atlantic hurricanes as my data set for this

project, but I have neither the time nor the patience for that. Instead, I’m

looking at only hurricanes who have been powerful enough to have their names

retired:

|

| There have been 77 retired names since 1954. One, Gracie (1959), is listed as retired by some sources but not others. Another, Allison (2001), was retired despite never actually becoming a hurricane. |

There are a lot of extremely strong hurricanes in this set,

but there’s still a very large number (there’s even a tropical storm!). I’m going to narrow it down even further, to

hurricanes that caused most of their damage to the United States. This

eliminates hurricanes like Mitch in 1998, but I’m investigating when the next

big hurricane will hit the U.S., not the rest of the Atlantic.

Now we can begin looking for trends. Hurricanes overall

appear to be getting stronger and it looks like there are more that have been

retired in recent years, but…

|

| R2 =0.07818 |

That’s not a very conclusive regression line, and

logarithmic or exponential lines don’t really fit either. While the numbers

from 2003-2005 are eye-catching (12 hurricane names retired in three years!),

2006 and 2009 did not have any hurricanes retired, and neither hurricane on

that graph from 2010 made landfall in the U.S..

On the other hand, there has been a small increase in total

named storms over the years:

|

| http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/timeline/61b5be0856ccb449ab4978b2909ae8d7.png |

There might be a bit of a cycle going on- in recent years, a

two to four year cycle of powerful hurricane seasons appears. 2008 had several

strong hurricanes three years after 2005, and 2009 had none after the weak 2006

season. But as we look back (and forward- just Irene in 2011), we can see that

this theory doesn’t hold.

How about ENSO? We covered this phenomenon in depth a few months back, and it would make sense. El Nino supposedly represses hurricane

growth, and our data supports that. Unusually strong El Nino effects match up

with unusually weak hurricane season.

The reverse of El Nino, La Nina, would then spur hurricane growth,

right? Not so fast- the data on hurricane seasons that correspond with La Nina

doesn’t provide a strong correlation either way.

The key to this problem would appear to be the 2005

hurricane season. It was unusual in many ways. By all measures, it was the

strongest hurricane season ever. Hurricane Emily was the earliest category 5

storm ever. Vince formed father northeast (into cooler waters) than any other

storm on record. Wilma strengthened ridiculously fast after its formation.

Hurricane Epsilon was the latest hurricanes ever, lasting deep into December.

Tropical Storm Zeta went all the way into January. And yes; those are Greek

letters, meaning that the 21 letters from the English alphabet were exhausted-

the only time this has ever happened. In all, the 2005 season produced 31

tropical depressions, 27 named storms, and 15 hurricanes (7 of category 3 or

above). It accounted for 3,913 deaths and over $150 billion of damage.

I can find just two unusual aspects concerning the climate

in 2005. The first is that El Nino was expected to develop, but didn’t. The

second is that the years leading up to it- 2002-2005- were four of the five

warmest years on record (at the time). Fourteen hurricane names were retired

for these four years, and the one other year in the top five was 1998, which

saw the wraths of Hurricanes Mitch and Georges. Did the heat finally reach a

climax in 2005, causing the extreme hurricane season? Maybe, but more likely

not. In the Pacific, 2005 was an average or below average year. (It should be

noted that 2006 was the most active Pacific season since 2000, however.)

Additionally, many of the years since 2005 have been warmer, and yet none of

them had hurricane seasons quite as strong.

Overall, I just can’t find a trend for powerful storm

season. Hurricanes are simply so unpredictable that a storm season predicted to

be “slightly above-average” can produce 28 named storms; the opposite can be

true as well. We don’t know when, specifically, in a season the next big

hurricane will hit, or even what year it will be.* We can make guesses, but

nature will laugh at us and prove us wrong anyway. The best we can do is

prepare for the worst and try to minimize the damage and loss of life.

*In 2011, Colorado State University, one of the leading

hurricane prediction centers, announced that it would no longer be releasing

quantitative forecasts six months prior to each season, as "...forecasts of the last 20 years

have not shown real-time forecast skill." Hurricanes are unpredictable

even for the professionals from a long distance away.

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

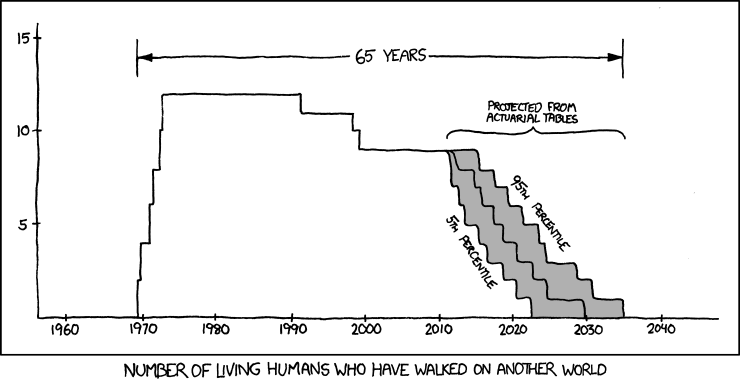

Will There Ever Be A Time When No One Alive Has Walked On Another World?

The death of Neil Armstrong brought out a lot of emotions in me. I wasn't around when he took his first steps on the moon, but I was certainly aware of the magnitude of this achievement. To be able to look up to the moon and know that he and eleven others had walked there, on that sphere so far away, was captivating.

The death of the last frontiersman also instilled a thought in my head, though. No one has walked on the moon in nearly forty years. Some of you may remember this profound post made by Randall Munroe on xkcd:

With no plans in the near future to revisit the moon- and with Mars still a ways off- there may soon be a time when there will be no one alive who has walked on another planet or moon. It's a sad thing to think about.

When will that be, if it happens? I don't have the time to look up actuarial tables, so I used the average life expectancies for people with ages equal to the remaining astronauts (as can be found on Wolfram|Alpha). I took an extra liberty and assumed that, on average, each of them are within the top 10% of the population in terms of health (astronauts must be fit, and their habits likely continue into an older age). I did not do any research into their individual health conditions.

I also feel like getting someone on Mars is a matter of when, not if. NASA doesn't have any sort of formal timetable out on this project, but I've heard 2030 as a ballpark figure by multiple sources. My goal is to discover the odds of any of the astronauts surviving to 2030.

The results are promising on this front. By the time 2030 comes around three astronauts in particular- Eugene Cernan, Charles Duke, and Harrison Schmitt- will be younger than the lifespan for the top 10% of people their age. Taking all the astronauts together, the average chance that any one of them will survive until 2030 is about 7%. All things considered, I'd say the odds are good that someone will survive until we set foot on Mars. Anything past that 2030 date, however, and the odds go sharply down. All of the astronauts will be pushing 100 by then.

I don't feel great about looking at "death rates" because there's hardly anything statistical about it. It all depends on your lifestyle and past, and for these astronauts, I'm sure there's a long, bright future still ahead of them. I mean no disrespect to anyone, especially Neil Armstrong.

America needs a new frontiersman now, and I'm sure NASA is hard at work on it. You could say our Curiosity needs to be satisfied again. Let us move forward to Mars, while we look backwards with fond memories of our missions to the moon. RIP, Neil Armstrong.

My data:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AnZrkjWWJajQdGlLMzFNWm1RUWFaZHJ5ZllRVkQ4c2c

The death of the last frontiersman also instilled a thought in my head, though. No one has walked on the moon in nearly forty years. Some of you may remember this profound post made by Randall Munroe on xkcd:

With no plans in the near future to revisit the moon- and with Mars still a ways off- there may soon be a time when there will be no one alive who has walked on another planet or moon. It's a sad thing to think about.

When will that be, if it happens? I don't have the time to look up actuarial tables, so I used the average life expectancies for people with ages equal to the remaining astronauts (as can be found on Wolfram|Alpha). I took an extra liberty and assumed that, on average, each of them are within the top 10% of the population in terms of health (astronauts must be fit, and their habits likely continue into an older age). I did not do any research into their individual health conditions.

I also feel like getting someone on Mars is a matter of when, not if. NASA doesn't have any sort of formal timetable out on this project, but I've heard 2030 as a ballpark figure by multiple sources. My goal is to discover the odds of any of the astronauts surviving to 2030.

The results are promising on this front. By the time 2030 comes around three astronauts in particular- Eugene Cernan, Charles Duke, and Harrison Schmitt- will be younger than the lifespan for the top 10% of people their age. Taking all the astronauts together, the average chance that any one of them will survive until 2030 is about 7%. All things considered, I'd say the odds are good that someone will survive until we set foot on Mars. Anything past that 2030 date, however, and the odds go sharply down. All of the astronauts will be pushing 100 by then.

I don't feel great about looking at "death rates" because there's hardly anything statistical about it. It all depends on your lifestyle and past, and for these astronauts, I'm sure there's a long, bright future still ahead of them. I mean no disrespect to anyone, especially Neil Armstrong.

America needs a new frontiersman now, and I'm sure NASA is hard at work on it. You could say our Curiosity needs to be satisfied again. Let us move forward to Mars, while we look backwards with fond memories of our missions to the moon. RIP, Neil Armstrong.

My data:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AnZrkjWWJajQdGlLMzFNWm1RUWFaZHJ5ZllRVkQ4c2c

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

How do the Olympics Affect the Presidential Election?

The United States puts a lot of time and effort into sporting events. In the US, the Super Bowl is the most watched television program ever (and also the second, and the third...). Athletes are some of the highest-paid people on the planet. In 2007, around 19 million people participated in fantasy football leagues across the country.

It would stand to reason that sports have some sway over the decisions people in America make. The biggest decision of all occurs every four years: the presidential election- and coincidentally, the election happens about three months after the world's biggest sporting event: The Olympics.

The question I intend to answer today is how much impact the Olympics have over the presidential election. Do incumbents win reelection more often when the U.S. wins the most golds? Do they receive a boost when the U.S. successfully hosts the games?

To compile this data I again used the IOC's medal ranking tables that I used in my first Olympic post. The U.S. has "won" (had the most gold medals in) 15 out of 24 summer Olympics. I did not include the winter games, as the more recent ones have occurred in non-election years. I also did not include boycotted games, games that took place after the election (1956) or the 2012 London games.

The results may surprise you. Of the fifteen times the U.S. came in first in the standings, the incumbent party was reelected eight times, and a new party was elected seven times. Similarly, of the nine times the U.S. did not come in first in the standings, the incumbent party was reelected five times, and a new party was elected four times.

When the U.S. has hosted the Olympics, the results have been more favorable: the incumbent party has won three out of four times. On the other hand, when the Olympics were cancelled during World War I and II, the incumbent party won each time, proving that the U.S. at least cares more about the war effort than sports.

Then again, when we boycotted the 1980 Moscow games, incumbent president Jimmy Carter lost to Ronald Reagan.

Speaking of the Soviet Union, I identified nine Olympics when the U.S. had a clear rival- in politics and in the medal count: Germany in 1936, China in 2008, and the Soviet Union from 1952 to 1988. The U.S. won more gold medals than their rivals just three times out of nine- yet the voting public didn't seem to care. The six "losses"are split evenly between the incumbent party and a new party, and the incumbents actually lost more often than not when the U.S. defeated their rival.

So what does this mean? The U.S. isn't as in to sport as one may think. We'll have to use other, more efficient means of forecasting the upcoming presidential election.

My data: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AnZrkjWWJajQdDcyV3kzWWVGaUVZcXRndnJ3M3MxMUE

It would stand to reason that sports have some sway over the decisions people in America make. The biggest decision of all occurs every four years: the presidential election- and coincidentally, the election happens about three months after the world's biggest sporting event: The Olympics.

The question I intend to answer today is how much impact the Olympics have over the presidential election. Do incumbents win reelection more often when the U.S. wins the most golds? Do they receive a boost when the U.S. successfully hosts the games?

To compile this data I again used the IOC's medal ranking tables that I used in my first Olympic post. The U.S. has "won" (had the most gold medals in) 15 out of 24 summer Olympics. I did not include the winter games, as the more recent ones have occurred in non-election years. I also did not include boycotted games, games that took place after the election (1956) or the 2012 London games.

The results may surprise you. Of the fifteen times the U.S. came in first in the standings, the incumbent party was reelected eight times, and a new party was elected seven times. Similarly, of the nine times the U.S. did not come in first in the standings, the incumbent party was reelected five times, and a new party was elected four times.

When the U.S. has hosted the Olympics, the results have been more favorable: the incumbent party has won three out of four times. On the other hand, when the Olympics were cancelled during World War I and II, the incumbent party won each time, proving that the U.S. at least cares more about the war effort than sports.

Then again, when we boycotted the 1980 Moscow games, incumbent president Jimmy Carter lost to Ronald Reagan.

Speaking of the Soviet Union, I identified nine Olympics when the U.S. had a clear rival- in politics and in the medal count: Germany in 1936, China in 2008, and the Soviet Union from 1952 to 1988. The U.S. won more gold medals than their rivals just three times out of nine- yet the voting public didn't seem to care. The six "losses"are split evenly between the incumbent party and a new party, and the incumbents actually lost more often than not when the U.S. defeated their rival.

So what does this mean? The U.S. isn't as in to sport as one may think. We'll have to use other, more efficient means of forecasting the upcoming presidential election.

My data: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AnZrkjWWJajQdDcyV3kzWWVGaUVZcXRndnJ3M3MxMUE

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

How to Become an Olympic Host Country

Yesterday, we concluded that Olympic host countries have an advantage over other countries. They tend to score about three places higher on the medal tables over other years. Today, we'll look at how to become an Olympic host country; specifically, what factors in the most to the IOC's decision about who hosts Olympic games?

This is what the IOC has to say about the process:

Obviously, a lot goes into this selection. There is no one factor that determines who gets to host the Olympics. Often, a city may be very well-qualified to host the games, but because several games have been hosted in the region recently, they will be rejected.

But if everything else was considered equal, is there something that can be considered a deciding factor?

I explored five independent factors: Population, Population Density, Size (Area), Human Development Index, and Gross Domestic Product (Total GDP). (Did I miss something? Let me know in the comments).

I searched each of these based on today's totals, not at the time the IOC awarded the Olympics. This might change the data slightly, but a good amount of countries (Belgium, Sweden) had relatively large development but not anymore, and a good amount of countries (Mexico, South Korea) had relatively small development but now are well-developed.

Based on today's statistics, here are the results:

Population, Area, Population Density

When the Olympics began around the turn of the century, many- but not all- the countries that hosted had high populations. The United States, France, Great Britain, Germany- all have large populations. And when you look at the data, it appears that a great amount of countries have high population, size, and area. However, there are many countries that also have a large size that have not hosted the games. India, Indonesia, and Brazil all have large populations and areas yet have not hosted an Olympics (Brazil, of course, will host 2016's summer games). Many African countries also have the same problem. Does it have to do with security? Or perhaps the lack of good facilities for athletes? Or maybe it's a matter of human development.

Human Development

It's understandable that the IOC would not want to shine a spotlight on countries that are not well-developed. An unstable country, such as Syria, over the seven-year period between a selection and the actual games, could spell disaster for the Olympics. While we can identify a more solid trend relating HDI to the Olympics, it's still not a very strong link. Mexico, Russia, and the countries making up the former country of Yugoslavia are not in the top tier of the HDI listing like most other Olympic hosts, and China does not even make the top 100. While many of the countries that host the Olympics do have very high Human Development Indices, it's not at all a solid trend (An r^2 value of 0.1). This leaves just one category:

Gross Domestic Product

The GDP of a country has the strongest identifiable link to hosting the Olympics. It's still not perfect, but it's much stronger than any other trend. What helps this variable the most is the United States. By far, the U.S. has the highest total GDP of any country and the U.S. has also hosted the most Olympic games. The trend isn't perfect, but it's much, much better than any other factor I can identify.

In the end, no one variable determines which country is awarded the Olympic games. But countries with a higher GDP have a much stronger chance. This is something to keep in mind, when, in 2013, the IOC makes their decision between Istanbul, Turkey; Madrid, Spain; and Tokyo, Japan, for the 2020 Summer Olympics.

Apologies for the late post tonight; tomorrow we'll look at how the Olympics affect politics.

My data and graphs:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AnZrkjWWJajQdFlxT3J5QW9vdmJsbFc5UkFnT0N2M3c

This is what the IOC has to say about the process:

"The IOC elects host cities following a two-stage process. Cities wishing to stage the Games in question become 'Applicant Cities'; the IOC Executive Board then selects a number of applicants to be considered 'Candidate Cities', from which one is chosen by a vote of the IOC session."

Obviously, a lot goes into this selection. There is no one factor that determines who gets to host the Olympics. Often, a city may be very well-qualified to host the games, but because several games have been hosted in the region recently, they will be rejected.

But if everything else was considered equal, is there something that can be considered a deciding factor?

I explored five independent factors: Population, Population Density, Size (Area), Human Development Index, and Gross Domestic Product (Total GDP). (Did I miss something? Let me know in the comments).

I searched each of these based on today's totals, not at the time the IOC awarded the Olympics. This might change the data slightly, but a good amount of countries (Belgium, Sweden) had relatively large development but not anymore, and a good amount of countries (Mexico, South Korea) had relatively small development but now are well-developed.

Based on today's statistics, here are the results:

Population, Area, Population Density

When the Olympics began around the turn of the century, many- but not all- the countries that hosted had high populations. The United States, France, Great Britain, Germany- all have large populations. And when you look at the data, it appears that a great amount of countries have high population, size, and area. However, there are many countries that also have a large size that have not hosted the games. India, Indonesia, and Brazil all have large populations and areas yet have not hosted an Olympics (Brazil, of course, will host 2016's summer games). Many African countries also have the same problem. Does it have to do with security? Or perhaps the lack of good facilities for athletes? Or maybe it's a matter of human development.

Human Development

It's understandable that the IOC would not want to shine a spotlight on countries that are not well-developed. An unstable country, such as Syria, over the seven-year period between a selection and the actual games, could spell disaster for the Olympics. While we can identify a more solid trend relating HDI to the Olympics, it's still not a very strong link. Mexico, Russia, and the countries making up the former country of Yugoslavia are not in the top tier of the HDI listing like most other Olympic hosts, and China does not even make the top 100. While many of the countries that host the Olympics do have very high Human Development Indices, it's not at all a solid trend (An r^2 value of 0.1). This leaves just one category:

Gross Domestic Product

The GDP of a country has the strongest identifiable link to hosting the Olympics. It's still not perfect, but it's much stronger than any other trend. What helps this variable the most is the United States. By far, the U.S. has the highest total GDP of any country and the U.S. has also hosted the most Olympic games. The trend isn't perfect, but it's much, much better than any other factor I can identify.

In the end, no one variable determines which country is awarded the Olympic games. But countries with a higher GDP have a much stronger chance. This is something to keep in mind, when, in 2013, the IOC makes their decision between Istanbul, Turkey; Madrid, Spain; and Tokyo, Japan, for the 2020 Summer Olympics.

Apologies for the late post tonight; tomorrow we'll look at how the Olympics affect politics.

My data and graphs:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AnZrkjWWJajQdFlxT3J5QW9vdmJsbFc5UkFnT0N2M3c

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)